Virginian Research

(This is from the August 24, 1905, edition of the Manufacturers’ Record, Vol XLVII, No. 6, pp. 131-133.)

From The Lakes, Through Coal, To The Sea.

Authoritative Story of the Deepwater=Tidewater Railway Systems in the Virginias.

[Special Correspondence Manufacturers’ Record.]

Charleston, W. Va., August 21.

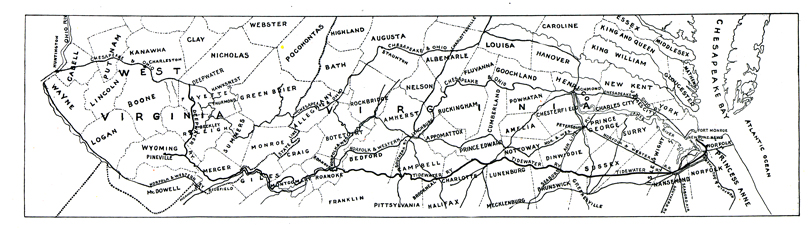

Nothing ever undertaken in the way of railroad construction is more novel or unique in its methods and in its history, or more “loaded” with possible effects on the development of a section, than is the Deepwater-Tidewater system of railways, now practically under contract between the town of Deepwater, W. Va., and the tidewater of Hampton Roads, Va., a distance of about 500 miles. From somewhere along the line an offshoot will ultimately appear, headed for some point on one of the Great Lakes of the North. Wherever it may land, the total length of the main line can hardly exceed 1000 miles. If Lake Erie is selected it will be much less than 1000 miles, all told. But that short trunk line will go through the heart of the best coking and steam coal fields of West Virginia -- a field nowhere surpassed in richness on the globe -- and it will be built to such grade and provided with such equipment as will enable it to haul coal to either lake or tidewater at a cheaper rate than is possible by any existing line.

Then the enterprise is novel and unique in that for the first time in this country, at least, it is being built as a whole, from starting-point to destination, without any reference to the local business of interior points. Deepwater itself, although at the head of navigation on the Kanawha river, 35 miles southeast of Charleston, is a mere whistling station on the main line of the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad. It is given a population of 135 by the census of 1900, and hardly any town of any importance outside of Roanoke is touched by the road between Deepwater and Norfolk. This is the first tidewater road to be built from the West to the East, and it is the first trunk line to be constructed with cash in hand, without one dollar’s worth of stock or bonds ever having been offered to the public. It will be the first realization of an old, old dream for a railroad through the West Virginia coal fields from the Lakes to the sea, and it will be along the only possible route left unoccupied. When it is built it will stand forth Minerva-like, complete and perfect, and there will not be a mile of track or a dollar’s worth of equipment that will not represent the very highest standards known to the railroad world of today.

Eighty-five-pound rails are being used; the viaducts are to be built of steel, with double-track capacity; the tunnels are cut five feet higher than those of other roads in this section, giving a 22-foot height instead of 17, and every feature of construction is subordinated to ease and cheapness of operation, without regard to initial cost. The only precedent in such railroad construction in the country is probably that of the Carnegie lines between the Lakes and Pittsburg. When the existing lines sought to dissuade Mr. Carnegie from constructing his road by offering to haul his ore at cost, his reply was that their cost price was not as cheap as he could haul the ores with the line he proposed to build. And what his road did to cheapen the cost of hauling ores this road proposes to do in the way of cheapening the cost of hauling coal. With the exception of eight miles, where the road crosses the Alleghenies, and where there is a 25-foot grade, there is nothing greater than a 7-1/2-foot grade, or two-tenths of 1 per cent. compensated, between the coal fields and tidewater, giving the road practically a level grade throughout almost its entire length. There will be three engine divisions on the road. On only one of them, the Allegheny or Princeton division, will there be as much as a 25-foot grade. To give some idea of the advantage this will mean, it may be noted that on the three engine divisions of the Norfolk & Western between the coal fields and tidewater there are places on all three of them where the grade is from 50 to 75 feet to the mile. What is called a ruling gradient is on the Norfolk & Western from 50 to 80 feet, while the maximum ruling gradient on the Deepwater-Tidewater is 25 feet. The total lift on the Norfolk & Western is over 4000 feet, while on the Deepwater-Tidewater it is but little over 1000 feet. A great part of this 1000 feet is in grades of less than 10 feet to the mile, while the greater proportion of the Norfolk & Western’s 4000 is in grades of 50 feet to the mile or more.

This is mentioned simply as a basis of comparison. The Norfolk & Western has grown into a great and profitable system, but its steep grades are known of all men. And although the new road gives promise of being able to haul coal cheaper than any other line, yet it is declared that there is no thought or intent that its operation will take any business away from either the Norfolk & Western or the Chesapeake & Ohio. It is the expectation that entirely new markets will be opened up by the new road. New York is at present almost clamoring for the smokeless coals of the New River-Pocahontas fields, and yet it is practically impossible for those coals to get into New York in any considerable lots. New York takes for consumption and distribution about 14,000,000 tons of steam coals in a year. New England, which takes about 5,000,000 tons of smokeless bituminous coal in a year, is the principal market for the coals delivered at tidewater by the Chesapeake & Ohio and the Norfolk & Western roads. The Deepwater-Tidewater system proposes to get into New York, and will make no fight for the New England trade.

That the Chesapeake & Ohio and Norfolk & Western do not exactly welcome the stranger into their midst might hardly be unexpected, nevertheless, and there is evidence along that line in some very interesting litigation, to be referred to later on. The Deepwater-Tidewater people maintain, however, that there is nothing piratical in their enterprise; that they are poaching on nobody’s preserves, and that in constructing their road they will bestow incalculable benefits on the section they open up and on the entire country as well by developing fields now purposely idle and by reaching markets in which West Virginia coals are now never seen. Moreover, interests friendly to or identical with those identified with the new road have holdings to a considerable extent in coal lands and properties in the territory opened up by the railroad -- a condition justifying, in their opinion, the construction of a road that will give ample tidewater transportation facilities to the products of these fields.

To comprehend the tremendous possibilities in the way of development, it is only necessary to refer to the located route of the Deepwater-Tidewater system. Starting on the Kanawha at Deepwater, so selected because from this place up Loup creek there is the only pass through the hills to the south that was not already taken up by the Chesapeake & Ohio, the route lies for 85 miles directly through the richest coal fields of West Virginia, with the Kanawha coals on one side and the New River-Pocahontas coals on the other, both, at these places; above the water line. There is thus given to the new road a mileage through the New River-Pocahontas smokeless coal fields of the State greater than the combined main-line mileage of the Chesapeake & Ohio and Norfolk & Western through the same fields. There are over 4000 square miles contiguous to the road that it can get into through spurs and branch lines, giving an opportunity for development of the most extensive kind. There has been some surprised comment heard on the fact that the new road has not followed the example of other lines, which through subsidiary companies have bought immense tracts of coal lands in the territory they penetrate. It is declared to be the studied purpose of the Deepwater-Tidewater to keep out of large land holdings. “I don’t regard it as right,” said President W. N. Page, in discussing the subject with me, “for a railroad company to paralyze development by buying up large tracts of land and holding them for the benefit of future generations. I want to keep out of coal lands. If we can give facilities and cheapness, our road will get business, I have no fear.”

The work of construction is progressing from both ends of the line. The road is completed from Deepwater to Paint Creek, giving 30 miles of road in operation. At Page, nine miles from Deepwater, there is a model coke-making plant of 505 ovens, the property of the Loup Creek Colliery Co., one of the enterprises with which parties interested in the road are identified. Mileage under contract at this end of the line -- the Deepwater, as the road is called to the Virginia border -- when it has been completed will take the line to the junction of Widemouth creek and Bluestone river, in Mercer county. The Tidewater end of the line is under contract for 105 miles west from Norfolk. Everything under contract will be finished this year and trains running. Track-laying will be commenced at Suffolk September 1, and it is the expectation that three-quarters of a mile a day will be laid on that end. The remaining mileage will be under contract before the summer ends.

As no plans have been perfected for the line to the Lakes, it is obviously impossible to chronicle anything other than gossip, except as to the fact that the road will eventually have a Lake terminus, which is a part of the avowed purpose of the company. The fact that a branch line is located down the Guyandotte river, leaving the main line at the month of Barker creek and running through Pineville, while right of way has been purchased as far down the Guyandotte as the mouth of Gilbert’s creek, give some color to the rumor that a line will be run down the Guyandotte river to its mouth at Huntington. It is authoritatively denied, however, that any location has been decided on, and until sufficient rights of way have been secured no definite announcement on the subject will be made. Although work on this portion of the line will proceed with quiet persistence, it is on the line between Deepwater and Hampton Roads that the greatest visible activity will prevail. In addition to road construction, work on the terminals at both ends will be pushed as rapidly as possible. At Deepwater the Chesapeake & Ohio and the Deepwater roads are together grading yards which will have a capacity of 400 cars. This work will be completed within 30 days. Equipment for the completed line was contracted for some weeks ago. It includes 500 coal cars, half of the steel underframe pattern, 100,000 pounds capacity, and half to be wooden hopper cars of 80,000 pounds capacity. The delivery of these cars began August 10, and will be continued till completed at the rate of 25 a day. Later the delivery of 100 box cars will begin. Contracts have also been placed for six heavy eight-wheel connected engines, two of which are being made by Baldwin and four by the American Locomotive Co. Two engines will be delivered in August, two in September and two in October. For the heavy traffic on the completed line engines of the Santa Fe decapod type may be selected, or possibly the Mallet compound, if they should be found a desirable type.

The tidewater terminals at Sewall’s Point are declared to be wonderfully fine terminals. Here it is claimed is the best harbor in Hampton Roads, “and Hampton Roads is the best in the world.” Here are 36 feet of water, and here is the holding point for United States and other vessels lying in the roadstead. At Sewall’s Point the railroad owns 520 acres of land with 3200 feet of deep-water front. It will have 36 feet of water at the head of its piers -- nothing less than 30 feet at low tide -- and there will be no channel dredging to be done. The improvements here will be made in accordance with the designs of the best engineering skill that money can buy, and it is declared that in completeness, convenience and the use of the latest devices and the most modern machinery no terminals in the world will surpass them.

The work under construction will cost about $36,000,000. With the line to the Lakes the entire enterprise, including everything except rolling stock and the Lake terminals, will cost some $50,000,000. And yet the companies doing this enormous work are capitalized at only $175,000 and have paid every bill without asking the public for one dollar.

Now, as ever since the road began, the question of consuming interest is, who is putting up this vast pile of cash? In the course of an extended talk I had with President Page the other day I learned some things about the road, but this was not one of them. While on matters of general policy and on the purely physical end of the enterprise Major Page was courteously communicative, so that I got straightened out on many of the rumors and newspaper reports I had run across, and the story here told is aimed to be in accordance with such confirmation and correction as I obtained from him, yet on the personnel side of the proposition he had not even the Biblical “yea, yea and nay, nay” to communicate.

“We are not courting publicity,” said he; “we are not offering to sell the public anything. When we do, we will then feel that the public has a right to know who is back of the enterprise. Just now we are building our road and paying our bills as we go along, and that we will continue to do. That is all I care to say on the subject.”

In newspaper comments that have been made on the enterprise it is declared without hesitation that Henry H. Rogers is the main backer of the road. A dozen years ago or so a number of New Yorkers interested themselves in the Gauley Mountain Coal Co., of which Major Page is president, and which has been successfully carrying on coalmining operations for some time with headquarters at Ansted. Subsequently these same interests increased their holdings by the purchase of 25,000 acres of land on Lower Loup creek. Among those interested was the late Abram S. Hewitt, and by his name the tract has been locally known. In this tract Mr. Rogers had interests; also the banking house of Morton, Bliss & Co. The Hewitt heirs, Levi P. Morton and the Bliss estate are, with Mr. Rogers, large owners in interest today. The Deepwater Railroad was first heard of when its charter was filed January 25, 1898. The route named was up Lower Loup creek to its headwaters; then down the White Oak fork of Dun Loup creek, near Glen Jean, to the station of that name on the DunLoup branch of the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad, a distance of some 30 miles. The incorporators were William N. Page, Charles P. Howard, Raleigh C. Taylor and George W. Imboden, Ansted, W. Va., and Thomas D. Ranson, Staunton, Va. Up to three years ago the company had constructed but four miles of road between Deepwater and Robson, which line was operated under contract by the Chesapeake & Ohio road. This fact has given rise, it would seem, to the report sometimes heard that originally the enterprise was a Chesapeake & Ohio proposition. It is declared by Major Page, however, that the project in its final entirety was the plan of the projectors from the beginning. From time to time additions to the original location have been filed, although there has been no increase in the capital of $75,000 named in the first charter, nor has the personnel of those whose names appear in public papers and reports of meetings been materially changed. The latest list of the officers and directors shows the officers of the Deepwater to be J. O. Green, president, New York; G. W. Imboden, vice-president, and Raleigh C. Taylor, secretary, Ansted, W. Va.; Geo. H. Church, treasurer, New York; William N. Page, chief engineer, Ansted, W. Va.

Of the Tidewater Railway, the Virginia end of the company -- organized in 1904 with $100,000 capital fully paid -- the officers are William N. Page, president; Thomas D. Ranson, vice-president, and H. J. Taylor, secretary, Staunton, Va.; Geo. H. Church, treasurer, and H. Fernstrom, chief engineer. The general manager of both lines is Raymond Du Puy, late vice-president and general manager of the St. Joe & Grand Island Railroad and president of the St. Joe terminals. His headquarters are in the Haddington Building, Norfolk. Mr. Fernstrom, also with headquarters at Norfolk, where the company has taken extensive offices, has recently succeeded C. P. Howard. He was for five years chief engineer of the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad, and is well known as one of the most eminent engineers in the country. The general counsel of both companies are Brown, Jackson & Knight of Charleston. Thomas D. Ranson, Staunton, is assistant general counsel of the Tidewater Railway Co., and division counsel are Loyall & Taylor, Norfolk; Robertson, Hall & Woods, Roanoke; R. C. & B. McClaugherty, Bluefield, and A. N. Campbell, Beckley, W. Va.

President Green is a son of the late Dr. Norvin H. Green president of the Western Union Telegraph Co., and a son-in-law of the late Abram S. Hewitt; Messrs. Imboden and R. C. Taylor are associated with Major Page in the management of the Gauley Mountain Coal Co.; Mr. Church, treasurer of both railway companies, is connected with the New York law firm of Shearman & Sterling, and is a director in the Amalgamated Copper Co., the Consolidated Gas Co., the Duluth, South Shore & Atlantic Railway Co., and a number of other corporations in which members of the Standard Oil Co. have controlling interests. Among directors of the railroad companies other than these is Mr. Erskine Hewitt, son of the late Abram S. Hewitt. The Virginia officers and directors have a standing in their State and section as eminent business men -- they are not “dummy” directors.

Looking through this list of names an analysis will enable one to discover why there has been a disposition to identify the Rockefeller-Gould railroad interests with the enterprise.

Of the possibilities this road furnishes for the consummation of the Gould plans for a network of railroads in West Virginia, I think I may find something of interest to write about later on. It certainly opens a wide field for speculation, and the biggest railroad interests in America are “taking notice” in the liveliest possible way. Just now there is much public comment as to the significance of the presence in West Virginia of Mr. J. M. Schoonmaker, president of the Pittsburg & Lake Erie road, and a man close to the counsels of the Vanderbilts. It is even positively declared in press dispatches that the New York Central lines and Pennsylvania interests have wrested from Gould the group of properties taken over by the Gould-Ramsey syndicate two or three years ago, generally described as the Little Kanawha properties. There are some facts connected with the formation and composition of that syndicate, however, which make these reports seem at least a trifle premature. As a matter of fact, the option given by Joseph Ramsey to the New York Central and associates has not yet been taken up, and it remains to be seen whether it ever can be. The great chess game between the Pennsylvania and Gould would hardly seem to have been half finished. That the Deepwater-Tidewater road will be a Gould ally, if it does not become a part of his system of roads, would by no means seem to be an unreasonable assumption. If this is true, it will strengthen his position enormously, not only by putting in his hands one of the best coal roads ever constructed into the heart of the Kanawha and the New River-Pocahontas coal fields, but by opening up the possibilities of connections and extensions which will give him everything he wants in the way of access to the Pittsburg coals of West Virginia, as well as lines from West Virginia into the city of Pittsburg and to the Lakes.

That obstructions should be put in the way of the construction of a new and independent railway into so rich a field as this is not to be wondered at, considering the limitations of human nature; the pains and expense taken by the Pennsylvania system to extend its “sphere of influence” so as to cover all the trunk lines of West Virginia; the successful efforts that had been made by the Chesapeake & Ohio management to thwart previous plans for the construction of independent lines, and the proud boast that so far no road other than the Chesapeake & Ohio has ever hauled a pound of coal out of the New River fields. Even up to recent years, however, it was almost the universal belief that no Deepwater-Tidewater Railroad ever would be built. “It was our salvation that they did not take us seriously,” said President Page to me. “It might have been impossible to construct the line if it had ever been believed that we could do it.” However, on principle, perhaps, the stranger road has had to contend for almost every foot of advance it has made, and even now is being obstructed in Norfolk by an attempt on the part of the Norfolk & Western to deny the Tidewater the almost essential privilege of grade crossings -- essential because belt-line connections could not be made from the elevated structure that overhead crossings would necessitate in that level country, there being nothing but grade crossings in Norfolk now, and because such overhead crossings would entail a worse than needless expense of about $1,000,000.

Up to the present time the Deepwater-Tidewater has scored an unbroken series of victories in the legal battles fought. The most unique of these contests, and one doubtless without a parallel in history, had to do with a tunnel the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad built, which in every feature of expense involved an outlay of some $60,000, and which the Deepwater-Tidewater people took away from them without paying one cent or indemnity, recompense or “salve” money. This tunnel is at Jenny’s Gap, which affords the only feasible pass by which the Deepwater road could get through the Guyandotte mountains from the headwaters of Coal river to the headwaters of the Guyandotte. In 1901 the road had extended its charter in accordance with plans now nearing completion, and after several surveys decided on the line which would require a tunnel through Jenny’s Gap. An earlier survey was found to be less advantageously located with reference to easy access to both the Kanawha and New River-Pocahontas coal seams, so that it became a matter of necessity to secure the present route. The Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad had filed a survey for an extension to and down the Guyandotte river to its Piney Creek branch line, in operation between Prince Station and Raleigh, the survey covering the same gap. In October, 1901, the Deepwater Company purchased right of way through Jenny’s Gap and got a deed for a location a mile and one-quarter in extent. The Chesapeake & Ohio had already begun construction on its line, having 16 miles of track laid. Denying that such a fragmentary location of a railroad was legally binding, the Chesapeake & Ohio instituted condemnation proceedings, got possession of the gap, built the tunnel and laid its tracks. It was only in February of this year that the matter was at last threshed to a conclusion in the Supreme Court, the final finding being that the Chesapeake & Ohio Company were trespassers, and, knowing conditions, the improvements they made were at their own risk and they were entitled to recover nothing. The Deepwater road did, however, permit them to recover their tracks, which have been taken up, and the Piney Creek extension must go down the Guyandotte by another route.

Meantime the Deepwater people had begun work on another tunnel on their right of way 100 feet distant from the one built by the Chesapeake & Ohio, in order to be prepared for emergencies. It was well on toward completion, but on securing the favorable decision work was stopped, and it will be held in statu quo till the anticipated time when a double track will be laid by the Deepwater-Tidewater. The finished tunnel is being cut five feet to conform to the grade of the Deepwater road. Otherwise five feet would probably have been cut above the present roof, as advantages of ventilation have decided the Deepwater engineers to give a height of 22 feet to all tunnels.

While this is the most picturesque of the fights the new road has had, it is only one of a large number of more or less importance. With the question of grade crossings disposed of -- and a victory is again looked for here, as the present status of litigation is an appeal to the courts by the Norfolk & Western from a decision by the Virginia State Corporation Commission entirely favorable to the Tidewater -- there will be nothing left in the line of serious obstructions, and the early completion of this phenomenal coal road from Deepwater to tidewater may be confidently expected.

Albert Phenis.